during the editing phase, including researching and writing the entire therapy arc and psychologist sessions, which are based on actual cognitive behavioral therapy. The submission draft of the book was lighter in tone. Maguire wasn't struggling quite as much at the beginning of the story, and although her journey to attempt to overcome her fear of being a bad luck charm went through largely the same task-oriented trajectory, it wasn't until the end of the book that she realized she needed the help of a professional therapist. You can

I thought it would be fun to share the original beginning to the story. If you were one of my

street team members then you might have already read this. Either way, if you've read the novel you'll recognize about 40% of these paragraphs from the final book. This is pretty common for me--to cut entire chapters but excerpt out certain passages that I think are particularly meaningful and fit them in elsewhere. Check it out:

I

didn’t blame myself for the first accident, or even the second one. After the

third one, I did what any rational twelve-year-old would do—I went to a fortuneteller.

Her eyes got wide as she flipped

over the tarot cards one at a time. I don’t remember exactly what she dealt,

but there were a lot of swords and everything was upside-down.

“Grave, very grave,” she muttered.

She grasped my hand and examined my palm, shaking her head in dismay. “You are surrounded

by darkness.”

“I’ve been in a couple of accidents.

People…got hurt,” I stammered.

“But this reading…” She sighed

dramatically and gestured to the five cards laid out in a cross formation. “It

says the worst is yet to come.”

After that, the bad dreams started. Four

years later, they’re still haunting me.

There are two in particular that I

have on a regular basis. One is about the car wreck, about plunging through the

guardrail and down the side of the mountain. It starts off just like I remember

the moments before the accident: me and my brother fighting in the backseat, my

dad and uncle laughing at us. But then instead of telling my brother to shut

up, I tell him he’s going to die. I tell them they’re all going to die. And

then I reach for the steering wheel. When the ambulance arrives, I’m covered

with everyone else’s blood, just sitting cross-legged in the carnage. Smiling.

The other recurring dream is of a

cemetery and three coffins placed side-by-side. The pallbearers come back with

a fourth coffin and everyone at the funeral turns and tries to stuff me in it.

I’m screaming and kicking, but no one seems to notice or care. They just pin my

body to the shiny satin interior until they can slam the cover shut.

Tonight I have the first dream.

I wake with a crushing sense of

dread wrapped around my middle, the shrill cry of the ambulance siren fading

away as light begins to filter through my rapidly blinking eyelashes. With

trembling fingers, I slip a battered red notebook out of the top drawer of my

nightstand and record what I remember. I call it my luck notebook, but it’s

more a ledger of unfortunate happenings and bad dreams. Nightmares can be a hint

of things to come, so on dream days I have to be extra careful.

Setting the notebook aside, I lift a

hand to my throat to make sure my mystic knot amulet is still in place. The

mystic knot is a Buddhist symbol of luck that I bought online. It’s supposed to

bring positive energy to every aspect of your life. Believe me, I need all the

positive energy I can get. I wear my mystic knot 24-7—when I’m sleeping, when

I’m showering, even in gym class.

Especially in gym class—high school

gym can be dangerous.

As a bonus, the amulet is made of

iron, which is said to repel evil faeries who cause bad luck. I don’t know if

there’s such a thing as faeries, but bad luck has to come from somewhere,

right? Better safe than sorry.

I knock three times on my wooden

nightstand and then dab a bit of jasmine perfume from a tiny heart-shaped vial on

each of my wrists. The manufacturers of the perfume claim it’s made with water

from a special Himalayan stream and has been blessed by Nepali monks.

Just one more ritual to complete

before I slide out of bed—my daily positive affirmation. I know it sounds cheesy,

but a lot of people swear starting your day with a positive thought makes a

difference and I’m in no position to ignore stuff that works just because I

feel lame doing it. Most people say something like: “Today is going to be a

great day.” I try to keep things a little more realistic, like: today isn’t

going to be as bad as that day at Celia Bittendorf’s sleepover party when

everyone but me started throwing up all over the place and Celia told her

parents I poisoned the cake and then her mom called my mom and I got picked up

at midnight and everyone at school avoided me for the rest of the year.

Okay, maybe that’s a little long.

“Today is not going to suck,” I

mutter.

Stretching both arms high in the

air, I yawn mightily and finally get out of bed. Standing in front of my

dresser mirror, I recite a Chinese good luck prayer eight times. (Eight is a

lucky number in Chinese). Then I make a half-hearted attempt to finger-comb my hair

and twist it back into a bun. That part’s not about luck; it’s just about

keeping my hair from taking over my face. I’ve got one of those manes that

everyone likes to ooh and ahh over, but no one really wants for their own.

Thick black hair that hangs to the middle of my back in corkscrew curls and

sticks out a couple of feet from my head if I don’t tame it down and tie it

back. Kind of like that old school guitarist, Slash, only I’m a lot smaller

than he is, so my hair looks even bigger.

I tromp down the hall and into the

kitchen in my pajamas. My mother is at the counter, cutting up a mango, the

baby monitor tucked in her front pocket. I watch her for a moment, listening to

the whisper of the knife blade as the slices pile up on the cutting board. If I

had to describe Mom in one word, it would be control. Controlled knife.

Controlled expression. Pressed pantsuit. Hair cut short enough to never be

unruly. Everyone needs to feel in control; we just go about it in different

ways. For Mom it’s clothes and hair, a second husband with a stable job, a

battery of tests early in her pregnancy to make sure my new half-brother Jacob

would be born healthy. For me it’s a notebook full of data, a series of good

luck rituals, and a predictable routine that I can plan for.

My stepdad, Tom, has his head buried

in a newspaper. He’s an engineer of some sort. Chemical? Mechanical? Honestly, I

don’t know, but then I’ve never made much of an effort to ask. Don’t get me

wrong--he’s not a wicked stepfather or anything. He’s basically cool. It’s just

even after five years of him being my stepfather, it still feels like betraying

my real dad to get too close to him.

I spoon some oatmeal into my

favorite bowl with the painted white elephants around the rim and take my usual

seat across from my half-sister Ellen. When my mom and Tom aren’t looking, I toss

a little salt over my left shoulder. Ellen catches me and giggles. “Maguire,”

she says in her high-pitched voice, mangling my name just slightly so it sounds

like Mack Wire.

“Shh.” I raise a finger to my lips.

Her bright blue eyes sparkle. She’s only four. She’ll play along.

Casually, I let my hand drop to my

chair where I knock three times. My rituals probably seem excessive, and I

guess they are. But you’d be excessive too if people’s lives were at stake. You

know how some people are magnets for trouble? I take that to a whole new

level—I not only attract bad luck, I somehow reflect it onto the people around

me.

Yep, I’m a bad luck charm.

It sounds a lot cuter than it is.

I was nine when the car accident

happened. My dad, Uncle Kieran, my brother, and I were heading home from a day

of hiking at a state park outside of San Luis Obispo, where I grew up. A scenic

road. A hot summer day. The perfect setting for a Sunday drive.

Or, as it turned out, a horror story.

Connor and I were fighting about this

boy who lived down the street when I saw the giant truck heading right at us. The

driver must have lost control of his rig as he navigated the twisting mountain road,

veering dangerously into our lane.

Dad tried to swerve onto the

shoulder at the last second, but we were driving along the side of a hill and

there was just a few feet of concrete and a flimsy guardrail. The back of the truck

clipped us and sent us straight through the guardrail and down the incline. We

flipped end over end and landed in a rocky ravine. Dad, Uncle Kieran, and

Connor were dead before the paramedics could get to us.

I didn’t even get hurt.

I was still in the ER when the

newspaper people found me. They called me the miracle kid. I’ll never forget

how they buzzed around me, asking prying questions about what I remembered and

why I thought I got spared. I had just lost three members of my family, and

these people wanted to talk about the luck of the Irish.

My mom tried to shield me from the

reporters but eventually gave up and posed with me for a few pictures so they

would go away. She said focusing on how I was alive would help everyone cope

with losing my dad and uncle, two of the town’s most decorated firefighters. It

didn’t help me cope. All I could

think was that I should have been nicer to Connor. He was just teasing me. How

is it something that feels so crucial one moment can seem completely trivial

after the fact? If I had known, I would have spent my brother’s last few

seconds on earth telling him how much I loved him instead of telling him I wished

he would shut his mouth for good.

The driver of the truck died too, so

we never found out for sure why he had lost control.

I never thought much about control

before that day.

Two years later, when I was eleven, a

rollercoaster I was riding careened off the tracks and crashed to the ground at

a nearby amusement park. That accident wasn’t quite as serious—at least no one

died—but every single passenger in our car had broken bones, except for me. Again,

I was completely unharmed. No one called me a miracle kid that time, but the

crazy lady who begs for change in front of the AM/PM called me a witch.

We moved after that.

There were other things too, like

the previously mentioned slumber party disaster. That’s what sent me off to the

fortuneteller and caused me to start keeping track of everything in my luck

notebook. But then three months ago, the house next door to us accidentally

burned to the ground from a candle I left lit on my windowsill. You wouldn’t

think a brick house could go up like a box of matches from one teensy dollar

store votive, but it did. The firefighters said they’d never seen anything like

it.

We moved again.

Mom said it was because Tom got transferred,

but I’m pretty sure it was because of me.

That’s how we ended up in Pacific

Point, a suburb of San Diego where tan, blond people seem to outnumber everyone

else three to one. It’s only my second day of junior year and already three

people have asked me if I’m a foreign exchange student.

“Maguire, don’t forget you have

tennis tryouts after school,” my mom says with entirely too much enthusiasm.

She fiddles with a piece of hair at the nape of her neck.

“Got it,” I say through a mouthful

of oatmeal. As if I could forget. The problem with tennis tryouts is that

they’re outside of my normal safe routine: walk to school, sit through classes,

walk home. How can I hope to control the situation if I don’t know exactly what’s

going to happen?

Tom takes his plate and mug to the

sink and rinses them thoroughly. “I hope the new racquet works out for you.” He

slides his now clean-enough-to-eat-off dishes into the dishwasher.

“I’m sure it’ll be great.” I force a

smile.

He and my mom bought me this top of

the line graphite-titanium-moon rock-bulletproof two-hundred dollar racquet. I

appreciate the gesture, but unless it’s going to play for me there’s no guarantee I’ll make the team. And unless it’s

magical, there’s no guarantee something bad won’t happen.

The oatmeal begins to congeal in my

stomach when I start brainstorming about possible accidents that could occur

during something as seemingly benign as tennis tryouts.

As you can imagine, once I accepted

the fact I was bad luck, I tended to shy away from group activities. And

groups. And activities. I traded dance lessons and the church soccer team for

running—something I could do all alone. I also started spending a lot of time

in my room, tucked under my covers reading books. There’s only so much damage a

book can do, and I wasn’t worried about hurting myself. The worst is yet to come. Accidentally hurting yourself is way

better than hurting other people.

I also started researching ways to

combat bad luck. Gran told me this story about evil faeries, about a man who

wished for something bad to happen to his neighbor. Apparently he didn’t really

mean it, but his words invited the faeries into his life and they never left. Sure,

Gran’s tale was probably complete fiction, but what if it wasn’t?

So I started out reading about

primrose and iron and how to keep the faeries away. Gradually, I widened my

search to cultures outside of my own, learning about herbs and chants and new

age-y things like yoga and positive affirmations. I even spent one whole summer

trying to de-curse myself with all-natural tonics and spells purchased on the

internet. I tried whatever I could do without a lot of explanation to my

mother. And anything I decided might have some positive benefit, I incorporated

into a daily routine. I had plenty of time to knock on wood and repeat good luck

chants since I’d quit doing much else besides going to school.

Sure, I got lonely for a while. But

getting invited to slumber parties just wasn’t worth the stress of wondering if

I might accidentally burn down the house with my flat iron or be the only

survivor of a freak sleepover massacre. And loneliness is just like everything

else—if you endure it long enough, you get used to it.

But when we moved to Pacific Point, my

mom finally decided I was spending too much time with my head in a book and

told me that this school needed to be different. I needed to get involved or

she was going to choose an activity for me.

Rule #1: Never let your mom choose

for you.

I imagine myself on the flag

twirling squad like Mom in her high school. Someone would probably get impaled.

At least tennis racquets are round, and presumably non-lethal.

“I can’t wait to hear all about it,”

my mom says. She fusses with Ellen’s hair while my sister drinks the leftover

pink milk at the bottom of her cereal bowl one spoonful at a time. “I hope that

practicing you’ve been doing pays off for you.”

She’s talking about me going to the

park and hitting the tennis ball against the wall of the racquetball courts. I

used to hit around with my brother when we were kids, but I’ve never had any

lessons or anything so I spent the last few days practicing as best I can. I have

no idea how good everyone else will be and I don’t want to be completely

humiliated at tryouts.

“And you said if I make the team I

can take your car to the away matches, right?” After the accident, I developed

a huge phobia of riding in cars. It took months of sedatives just to be able to

ride with Mom. There’s no way I’d survive being a passenger on a bus full of

kids.

My mom and Tom exchange a glance but

he doesn’t say anything. “I don’t see why not,” my mom says. “I won’t be going

back to work for a while.” She’s on maternity leave from her job as a physical

therapy assistant.

“If I don’t make the team, can I have points for effort and then go back

to my usual routine?” I ask hopefully.

“No,” Mom says firmly. “Trust me,

honey. These are the best years of your life. You’ll thank me for this

someday.”

“If these are the best years then

someone needs to just kill me now,” I mumble. She doesn’t know what high school

is like these days—people obsessing about extracurriculars and AP classes and

padding their college applications. It’s all about what you have and where

you’re going. No one seems to notice who you actually are. And is it me, or is

my mom the only mom in the history of ever who told her kid to spend less time

reading and more time being social? Doesn’t she know the chances of me getting

drunk, pregnant, and/or arrested are much lower if I never leave my room?

A mix of wailing and static bursts

from the baby monitor.

“And that’s my cue,” Tom says

jokingly, pretending like he’s racing for the door.

My mom smiles. “I’ll get him. You go

ahead.”

“If you’re sure.” Tom kisses my mom,

ruffles Ellen’s hair, and gives me a wave. “Knock ‘em dead, Champ,” he says.

Grabbing his keys from the table, he heads off to work.

I slide my chair back from the table

and mutter something about finishing getting ready. “Dead” is not a word I want

associated with today.

|

| Graphic by Emilie from Canada |

If you want to read more deleted scenes, you can check out

Maguire and Jordy practicing tennis at the local tennis club, or

Maguire and Jordy's sister trying to hide Maguire from Jordy's mom. I have over 100 pages of cut scenes from

GIRL AGAINST THE UNIVERSE and I will be sharing more of them in the future, both on this blog and over at my

Wattpad account.

BONUS: Are you a fan of dark, action-packed stories?

Click here to read the beginning of my twisty mystery VICARIOUS, releasing August 16, 2016 from Tor Teen.

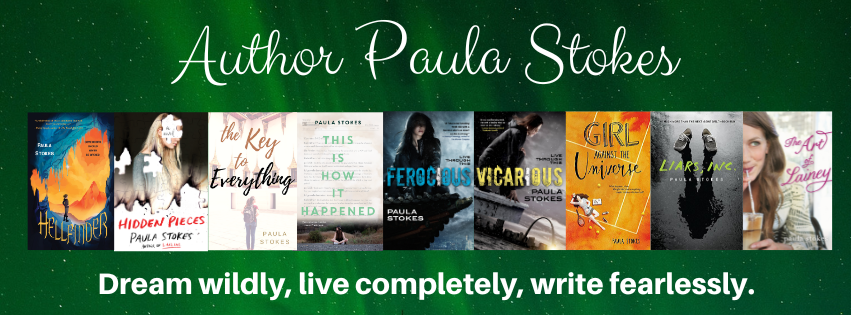

For this international giveaway, the winner will have a choice of a $25 B&N gift card, or a signed copy of any of the books you see in this post. (For Ferocious and TIHIH, you'll receive a signed ARC.) You can earn points for reviewing any of my last four novels--Vicarious, Girl Against the Universe, Liars Inc., and The Art of Lainey. You can also earn points just by tweeting or by leaving a comment about how to encourage readers to write reviews.

For this international giveaway, the winner will have a choice of a $25 B&N gift card, or a signed copy of any of the books you see in this post. (For Ferocious and TIHIH, you'll receive a signed ARC.) You can earn points for reviewing any of my last four novels--Vicarious, Girl Against the Universe, Liars Inc., and The Art of Lainey. You can also earn points just by tweeting or by leaving a comment about how to encourage readers to write reviews. 1. If I think your review is fake or plagiarized (meaning that you copied someone else's review, not that you used quotes from the book--that's totally fine), I will disqualify you from consideration without notification.

1. If I think your review is fake or plagiarized (meaning that you copied someone else's review, not that you used quotes from the book--that's totally fine), I will disqualify you from consideration without notification.

1. Pretend you are an author writing an official blurb for the book jacket. What would you say to the world about this book if you had to condense all your thoughts into one or two sentences?

1. Pretend you are an author writing an official blurb for the book jacket. What would you say to the world about this book if you had to condense all your thoughts into one or two sentences? 5. Choose your favorite quotes from the book. Tell how each

5. Choose your favorite quotes from the book. Tell how each